As more and more adults get vaccinated against the COVID-19 virus — and more and more students cautiously return to some form of in-person schooling — the desire to “get back to normal” feels like the irresistible lure of Spring after a long and lonely winter.

Tempting as it may be, however, the barrage of warnings we have tried to wish away — spoken in the language of fires, floods, and invisible pathogens — make clear that the norms of the past are no longer tenable.

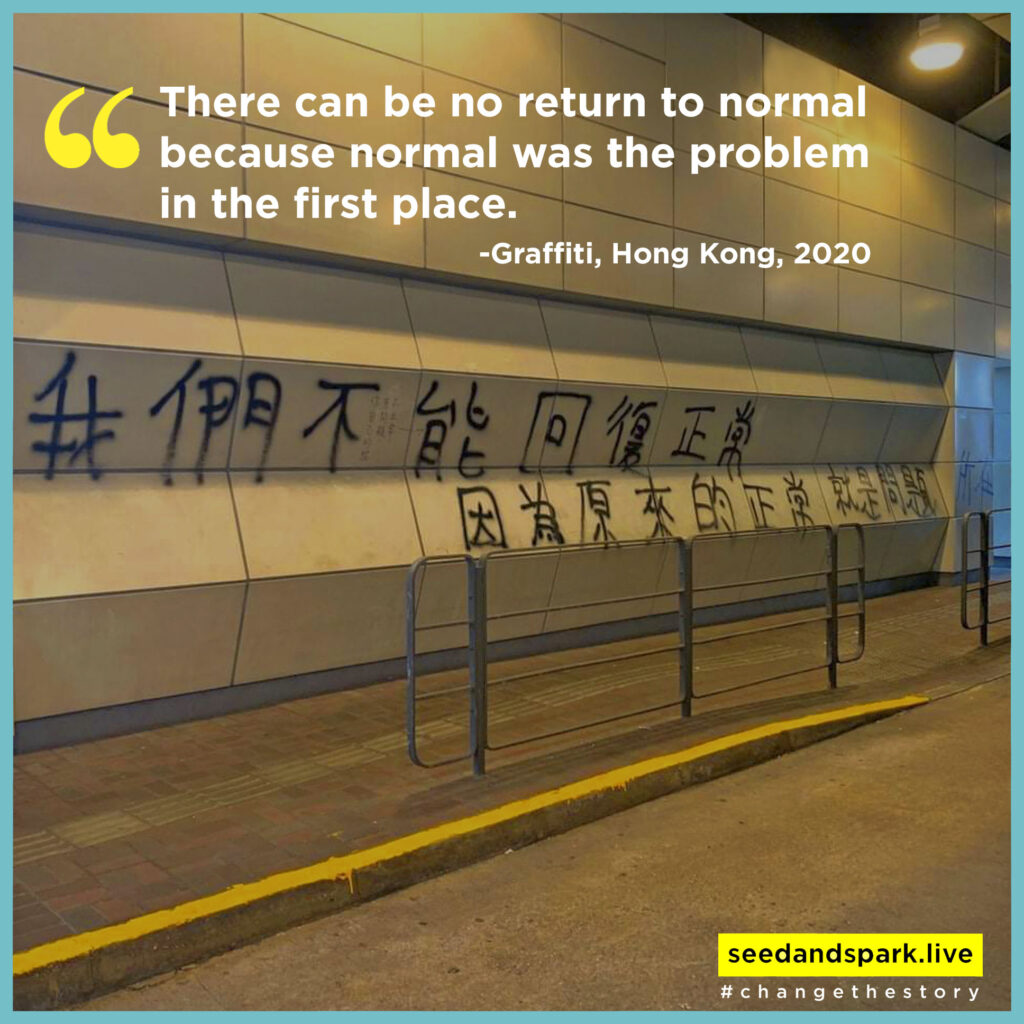

There can be no return to normal, because normal was the problem in the first place.

This is the hindsight of 2020.

To heed it, however, we must acknowledge the ways our common public world has shifted — and then we must shift the way we think about the structure and purpose of our common public schools.

Consider this: whereas in 1500, we produced goods and services worth about $250 billion in today’s dollars, today it’s $60 trillion — a 240-fold increase.

As a direct result of that conspicuous consumption, one-third of the Earth’s land is now severely degraded.

There are half as many animals in the world today as there were in 1970.

And we’ve used more energy and resources in the past thirty-five years than in the previous 200,000 — the total amount of time that homo sapiens have been alive and kicking.

Against these odds, and in the wake of all we’ve been through, it’s easy to feel hopeless. And yet as environmentalist Bill McKibben puts it, “the great advantage of the twenty-first century should be that we can learn from having lived through the failures of the twentieth. We’re able, as people were not a hundred years ago, to scratch some ideas off the list.”

When it comes to our nation’s schools, then, what ideas should we scratch off the list? And what, ultimately, is the shape of the change we seek — in our schools, our civic structures, and ourselves?

To orient us for the long journey ahead, we need four new rules of the road — and four new metaphors to use in redesigning how we learn and live:

- SCHOOL AS ECOSYSTEM

For generations, schools and universities have looked and felt the same because of the ways our “sacred cows” of education have kept us trapped in boxes of our own making.

School is a place, not a mindset.

Work must be graded to become meaningful.

Students are best sorted by age.

And so on (& on & on).

In the span of a year, however, COVID’s complete disruption of our traditional patterns has forced us to question these assumptions on almost every front.

What if school was a mindset?

What if the work itself was meaningful?

And what if we thought about learning design less mechanically, and more emergently?

Of course, this is already happening in many schools and universities all over the country (and your neighborhood Montessori school has been acting this way for the better part of a century). But in order for more students and communities to have the same experience, we need to stop unconsciously designing schools as assembly lines, and start consciously designing them as ecosystems.

The good news is that nature has shown us what living systems require in order to thrive — we’ve even written an entire (free) book about it . And although it may seem counter-intuitive, a central lesson is that anything that disturbs a living system is also what helps it self-organize into a new form of order.

Growth, in other words, comes from disequilibrium, not stasis.

So while it’s unrealistic for most of us to just burn the whole thing to the ground, what we can do is take a critical look at our own school’s sacred cows and then decide strategically which ones are both the greatest hindrance to our work — and the easiest to get rid of. (Here’s a helpful way to do this together).

Then, over time, this gradual approach to structural change can start to chip away at the foundations of the systems that have held us prisoner for too long.

Speaking of which . . .

- SCHOOL AS ACORN SEED

While it has been true for some time that the pace of change in our modern world requires long-range thinking and planning (see, e.g. Blockbuster v. Netflix), the catastrophic impacts of COVID-19 are demanding that we make a radical shift in our relationship to time — away from the seductive lure of short-term, election-cycle solutions, and towards a less certain, more generational worldview and way of being.

In short, as Roman Krznaric argues in his vital new book, The Good Ancestor, “we have to think long” — something we humans can do, just not very well.

It’s hard to think long when the world around us is driven by short-term dopamine-driven feedback loops. Yet our ability to activate what Krznaric calls our “acorn brain” is what will determine whether we can meet the existential risks that surround us, from climate to coronavirus. “The challenge we face is to amplify our acorn brains and release their dormant power,” he says.

In which case, we need less five-year plans — and more fifty-year intentions.

This is not a new idea. It is, in fact, a feature of indigenous cultures the world over. The Iroquois, for example, held that any decision made today should result in a sustainable world seven generations into the future.

Imagine if the Seventh-Generation Principle were a part of our future decision-making in schools and universities?

It would probably result in less swimming pools, and more “living schools” (such as this one in Chicago, which is being designed and built for the same per-pupil expenditure as any other public school in the city).

And it would definitely result in a radical shift in what we define as the end-goal — away from just being a good employee, and towards being a good ancestor.

- SCHOOL AS HORIZON LINE

As Kznaric reminds us, “we are the inheritors of gifts from the past.”

Consider the gift of Jonas Salk, the scientist who, after a decade of experiments, created the first polio vaccine — and then refused to get his invention patented so more people could benefit from it.

As Salk said, “The most important question we can ask ourselves is, ‘Are we being good ancestors?”

For too long, we have ignored this question at our peril. As cultural anthropologist Wade Davis explains, our current patterns of human behavior expose the fallacy that it was ever possible to achieve infinite growth on a finite planet. It is, he warns, “a form of slow collective suicide, and the logic of delusion.”

Yet we see evidence of our delusion in every direction.

In smoke-clogged Chinese cities, giant LED screens show daily videos of the sun rising.

In American schools and classrooms, it has become commonplace to have “active shooter” drills.

And people touch, swipe and caress their phones almost 3,000 times a day.

Is this the future we wish to resign ourselves to — even after the first global pandemic in a century?

What if, instead, by using our acorn brains and letting nature’s design principles be our guide, we committed to a course-correction in the service of a different story, and a different way of learning and living?

In our schools and universities, the central contribution to such an audacious goal would be to start crafting fifty-year strategic intentions with the primary goal of creating good ancestors.

With that as our goal, we would need to design everything differently — our spaces, our cultures, our structures and our pedagogies. But in the spirit of a true long view, we wouldn’t have to do it all at once.

- SCHOOL AS TROJAN HORSE(S)

Long before there was a global pandemic, other industries were already making proactive pivots away from their timeworn traditions. As Eric Ries explains in The Lean Startup, “planning and forecasting are only accurate when based on a long, stable operating history and a relatively static environment. Startups have neither.”

Neither do schools and universities.

What our institutions of learning do have, however, is the chance to learn from other industries.

We can, as Bill McKibben said, scratch certain ideas off the list.

And when it comes to a task this massive — resisting the lure of our sacred cows, adopting a long view, and/or changing the central goal of schooling itself — we must stop making comprehensive plans, and start making constant adjustments through what Ries calls the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop.

It works something like this:

- Try lots of things (A day with no passing bells! A weeklong course! A month with no letter grades!)

- Test them out in short-cycle, low-stakes environments

- Let people opt into being part of the experiment (or watching from a distance)

- Pay attention to what works (and what doesn’t)

- Abandon the things that don’t work

- Double down on the things that do

- Follow the energy

- Rinse. Repeat.

As Ries puts it, the idea is to start building “minimally viable products, or MVPs”

as quickly and imperfectly as possible. “It should feel a little dangerous,” he adds, “but in a good way.”

This should be our post-COVID goal together: to build a thousand Trojan Horses – future seeds of potential creative destruction that can, when the time is right, assume a different form, attack our most intractable rituals and assumptions about schooling, and usher in a different way of being that is more in line with both the modern world and the modern brain.

Simply put, the days of letter grades, two-dimensional transcripts and “senior year” are numbered. We don’t need to get rid of them all right now – indeed, the time it will take for the larger systems and structures of K-12 and higher education to adjust to a new ecosystem almost require schools to cling to these trappings a while longer.

But make no mistake – much of what we have come to find most familiar about public education will, in due time, go the way of the 1960s-era department store (and, one hopes, the coronavirus itself).

So let’s change the story of the way we live and learn: by using nature as our guide, activating our acorn brains, making decisions for our great-great-grandchildren, and sowing the seeds of our own creative destruction — one slightly dangerous Trojan Horse at a time.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

Recent Comments