In Australia, the country of his birth, Thanh Bui learned early on that kids who looked like him faced two possible paths.

On one, traversed by the only other Asian student in his school, the cold sting of isolation and ridicule awaited. On the other, however, came the assimilatory embrace of knowing you were “one of the lads.”

For Bui, youthful, outgoing, and kinetic, it was an easy choice — one that would take him to heights his immigrant parents could never have imagined: first, playground popularity and acceptance, and then, eventually, global celebrity and superstardom.

The only requirement was that he suppress his Vietnamese identity.

It would take decades before Bui understood the true cost of his unconscious choice.

And it’s why he’ll spend the next decade planting seeds that he hopes can one day frame new paths, and new choices, for a new generation of Vietnamese children.

Recently, amid the symphony of barking dogs and the aromatic smell of diesel fuel, Bui sat on a fishing boat atop the muddy waters of the Mekong River, contemplating how his family’s journey had begun in this exact spot, a lifetime ago.

This was where his parents, along with eighty-five tightly-packed strangers, had summoned the courage to leave the country of their birth in search of a better life.

“They were the age then, 28, that I was when I first came back,” Bui said. “They had no education, no money, and nothing but the clothes on their backs. That’s why I wanted to come back here. I wanted to know exactly the place they had left.

“When you know where you’re from,” he said slowly, “there’s this sense of humanity that sweeps through you. I don’t think you’re ever O.K. until you know exactly where you’re from — and I’ve been on that journey my whole life.”

For anyone who is the child of immigrants, Thanh Bui’s journey will feel familiar. Although he grew up in Adelaide, a cosmopolitan city on Australia’s southern coast, Bui’s early experiences were limited to the dusty farm where his father picked potatoes. When the crop was wiped out one year, Bui’s parents packed what little they had to travel 700 kilometers further south, to the capital city, Melbourne.

Through a network of fellow immigrants, Bui’s parents found a job making jeans. To encourage her two sons, Thanh and Tan, to pitch in, their mother promised one penny for each pocket they sewed. As they worked, Bui recalls, “my brother and I heard every day that the only way to elevate oneself is through education. And although we were allowed to spend our earnings on jellybeans, every dollar my parents saved went into our education.”

At home, the Bui brothers led a life that was disciplined, directed, and thoroughly Vietnamese. Yet Thanh recalls “starting to feel this sense of not belonging anywhere, which left me wondering, ‘Who am I?’ But my father always said, ‘Son, I almost died three times getting out. The last thing you’re going to do is disrespect me and your ancestors by not knowing your language.’”

Eventually, Thanh earned a full scholarship to a prestigious boys school in Melbourne. His parents were thrilled, but Thanh remembers “feeling so out of place, like all eyes were on me. That started my whole understanding of how I fit in. I had to learn how to be an Australian.”

At the same time, Thanh was realizing that the dreams he held for himself did not align with the dreams his parents held for him. “Ever since I was little,” he explained, “I had the sense that music was part of me, that it could take me to this other world that I’d never visited before.”

His parents encouraged him to pursue his artistic side — as an extracurricular activity. But by the time he was 17, Bui’s talent had yielded some enviable choices, from pursuing a college degree on full scholarship, to becoming the lead singer of a band on the cusp of its inaugural Asian tour.

For Thanh’s parents, the choice was simpler: doctor or lawyer.

“You could see the pride in their faces,” Bui recalled. “They’d worked their whole lives for this, they’d sacrificed everything for this, this moment. This was the achievement.”

But Bui decided he had to follow his true path. “So I took a deep breath, I swallowed, and then I said the words that I knew would break my parents’ hearts:

“‘Mom and Dad, I want to be an artist.’”

Eight years would pass before he returned home again.

He traveled all over the world.

He started songwriting.

He nearly won Australian Idol.

And then, in 2010, at the height of his fame, he was invited to visit Vietnam on an open ticket — to meet with producers, record some tracks, and see what happens.

Three years later, he was still there — performing regularly as a solo artist, hosting the country’s most popular TV show, and beginning to feel accepted for the first time: a Vi?t Ki?u returning to his roots.

Yet his time in the country of his ancestors had made two things clear: the first was the complete absence of infrastructure to support Vietnamese artists. “Music at that time was an elite product few people had access to,” Thanh explained. “In a country of 95 million people, there are only a handful of people pursuing careers in music. And there’s talent here — but if talent doesn’t meet opportunity, then it’s nothing.”

The second epiphany was more personal. “I’d been shuttling between two homes for three years, trying to figure out what it meant to be Vietnamese and Australian in a world that was so globalized, and how to reconcile these different sides of myself. That’s when I realized that if I ever wanted to do so, I needed to move here for good. I needed to go all in.”

And so, on January 1, 2013 — Thanh Bui moved permanently to Vietnam to open the SOUL Music & Performing Arts Academy, a school that could stitch together both the modern and traditional sides of Vietnamese identity in order to “bring the soul back into our music.”

It was a rocky beginning.

At SOUL’s first open house, even though a thousand people came through the door, just fifteen registered for classes. “It was a stab in the heart,” Bui says. “Everyone was telling us it wouldn’t work. And in that moment the numbers reflected that. But it helped me understand the local context of the families we were trying to reach. We were still too Western-leaning. Parents wanted their kids to be singing in Vietnamese.”

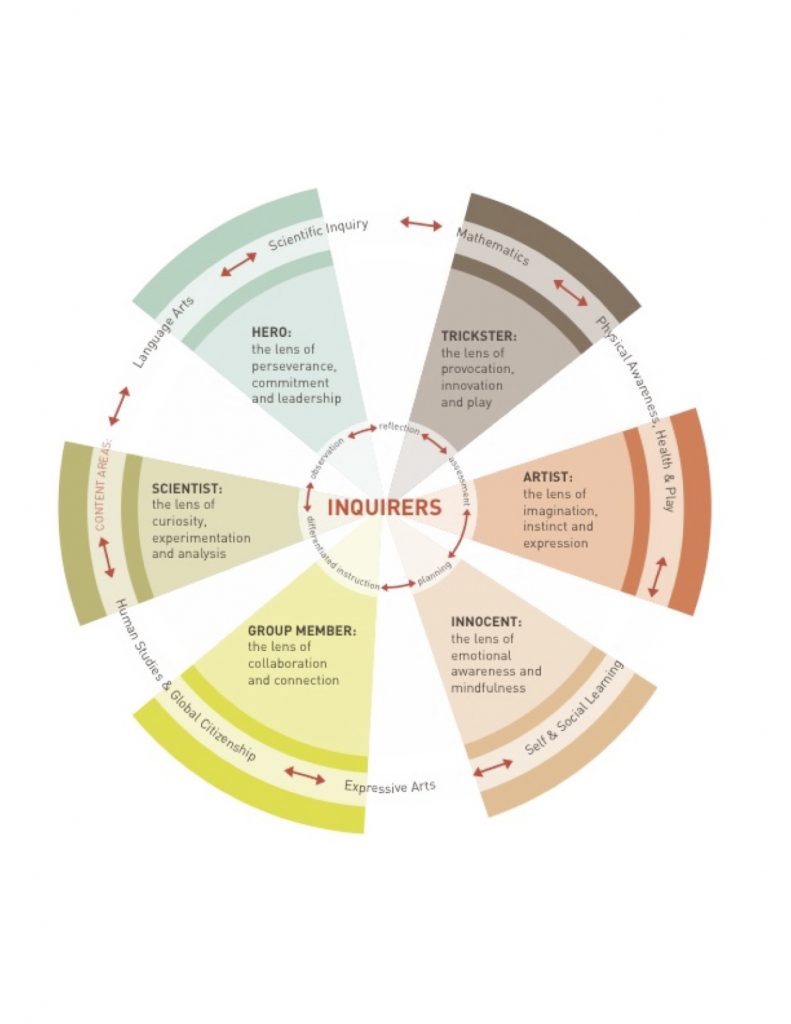

So Bui and his partners tweaked the course offerings, and gradually their student roster grew. “Our formula was to bring the world’s best ideas about artistry and craft to Vietnam, and then localize it,” he explained. “What was missing in Vietnam was a different sort of advocacy for the arts — to make them a vital part of a child’s holistic development: to be global citizens with local values.

“Vulnerability, for example, is a Western concept; ‘saving face’ is a Vietnamese value. The modern identity requires elements of both. So we use the arts to give kids the courage to find their own sense of themselves. Ultimately that’s why we exist — to inspire the next generation to be unafraid, and to find and use their voice.”

One weekday afternoon, amidst the patchwork of old French colonial and modern buildings that make up the SOUL campus, fifteen-year-old Bao Tan provided a walking embodiment of her school’s founding purpose. With long black hair, steady eyes, and a smouldering intensity, Bao recalled passing the school everyday as an eight-year-old, and “wondering about it.” Then she started writing songs, “and saying all these things I hadn’t been able to say in the past,” and she registered for every class she could take, from traditional singing to hip-hop dance. “All these things had been inside of me for so long,” Bao explained. “I’ve discovered that music is a part of me. I can’t say that I’m an extrovert but I feel like I have lots of things to say but I don’t know how to express it. And sometimes I really feel lonely, but not really because music is besides me.”

As a swirl of students around her — from infants to teenagers — arrived for their afternoon classes, Bao reflected on her generation, and what music can provide. “A lot of teenagers nowaday, not all the time do we know what we really want. We don’t really know what we want to do and pursue — so it’s really hard for me personally. I feel like sometimes I’m just scared that if I speak, will people judge me? You’re supposed to listen to your parents. But what are the other ways I can learn to explore myself? By speaking for yourself now, you really know what your identity is. When you look at me, what do you think I am — and is it the way that I think I am?

“A lot of parents in Vietnam, they raise their kids to just be a businessman or a lawyer. But there are lots of kids out there just like me. They want us to live in the safety zone. But for me, each of us has something — we’re still growing mentally and physically. They want to keep us in a frame in order to keep us safe. Music doesn’t fit into that frame.

“But music reminds me to slow down. Just be yourself. Just be Bao Tan. Just be who you want to be.”

A decade in, Thanh Bui now sees a future in which the lessons of SOUL can be applied to millions of Bao Tans, nationwide. In 2020, he opened a preschool that was designed in direct partnership with the pioneering educators of Reggio Emilia, Italy — one he hopes can provide a template that, in time, will transform early childhood education across the country. He has partnered with a Finnish University, Turku, and Harvard’s Project Zero, to think through issues of accreditation and assessment. Instead of trying to invent everything from scratch, he has contracted with existing curriculum providers, such as the German program Kindermusik, which introduces infants and toddlers to music. And he has begun constructing a one-million-square-foot “learning city” that brings together a K-12 academy, a college, a performing arts academy, and a sports and entertainment complex.

“The world is changing,” he said amidst the din of passing motorbikes, taxis and dust. “So must the purpose of school. We have to reconnect the artistic and scientific sides of ourselves: artist and businessman. Dancer and Engineer. Children of Vietnam and citizens of the world. If we’re serious about changing the way the world sees us and the arts, we have to build a new ecosystem that puts creative education at the heart of learning.

“We are a country that is not afraid to look forward. But social mobility is still very difficult here. My parents felt that sense of helplessness. ‘Where is home? What’s going to be the future?’ But if we can give access to the arts to every kid in this country, we can help them understand their roots and develop a more holistic viewpoint on life.

“Not knowing who you are, not knowing your purpose, that’s the biggest problem in the world. This whole understanding of who am I? Straddling between different cultures and different sets of identities. That’s something we can all relate to in this modern interconnected world.”

As Thanh spoke, a young boy’s voice could be heard from one of the school’s practice rooms. He was singing a traditional Vietnamese ballad, beautiful and slow, and the sound of it brought tears to Thanh’s eyes.

“We’ve been at war with ourselves for a long time,” he continued, running his hands through a pompadour of thick black hair. “But the last 45 years have provided an unprecedented period of peace. The modern byproduct of that are people like myself, who can bridge the two worlds. We share the same story. And we’ve all been searching for that pathway home to understand who we are and what we stand for.

“When people think about Vietnam, we don’t want them to think about the war anymore; we’re tired of that. It’s time for the new stories — the stories of hope.”

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

Recent Comments