Gina Farrar is not your typical New York City school leader.

For starters, she’s from the deep South — although any remnants of a Southern twang have long since disappeared. She’s also quiet and friendly — the sort of person who likes going to restaurants in the middle of the afternoon, or smiling at kids on the train.

Then there’s her formal education: a double major in Dance and Mathematics, followed by a PhD in Psychology. Although this is where, if you follow the pattern, Gina Farrar’s career path starts to make sense. “What attracted me to math and dance is that each is a puzzle,” she told me one recent fall morning. “The ways that math is a puzzle are obvious, but ballet is a puzzle, too — how your body fits together, how the steps fit together. And there’s a lot of technique involved, but it’s only when you master the technique that you can soar.”

The same can be said for Blue School, a decade-old independent school in lower Manhattan that Gina leads, and which was created by the founders of Blue Man Group, the global theatrical phenomenon that was designed to inspire creativity in both audience and performer.

To many, that riddle — how to inspire creativity — is the Holy Grail of school reform in 2018. Back in 2006, however, it was little more than a nugget of an idea that turned into a small parent playgroup in lower Manhattan. Soon thereafter, it grew into a full-blown school — albeit one whose theories about teaching and learning were both intriguing and unproven. And now, Blue School has evolved into something I’m not sure I’ve seen anywhere else in my travels — a school community that is, both literally and figuratively, a living organism, and a theory of learning that has, over a decade of strict scrutiny, constant tinkering, and loving care, developed a full-blown pedagogy as worthy of replication as its more famous single-name forebears:

Montessori. Reggio. Waldforf.

Blue?

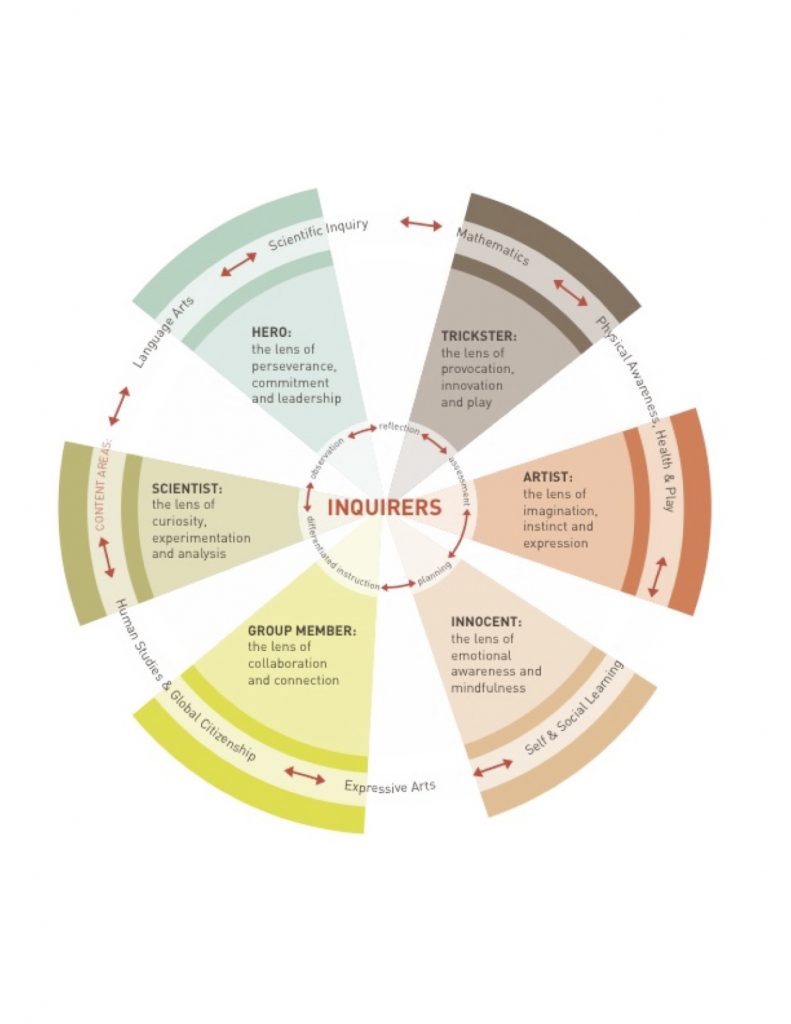

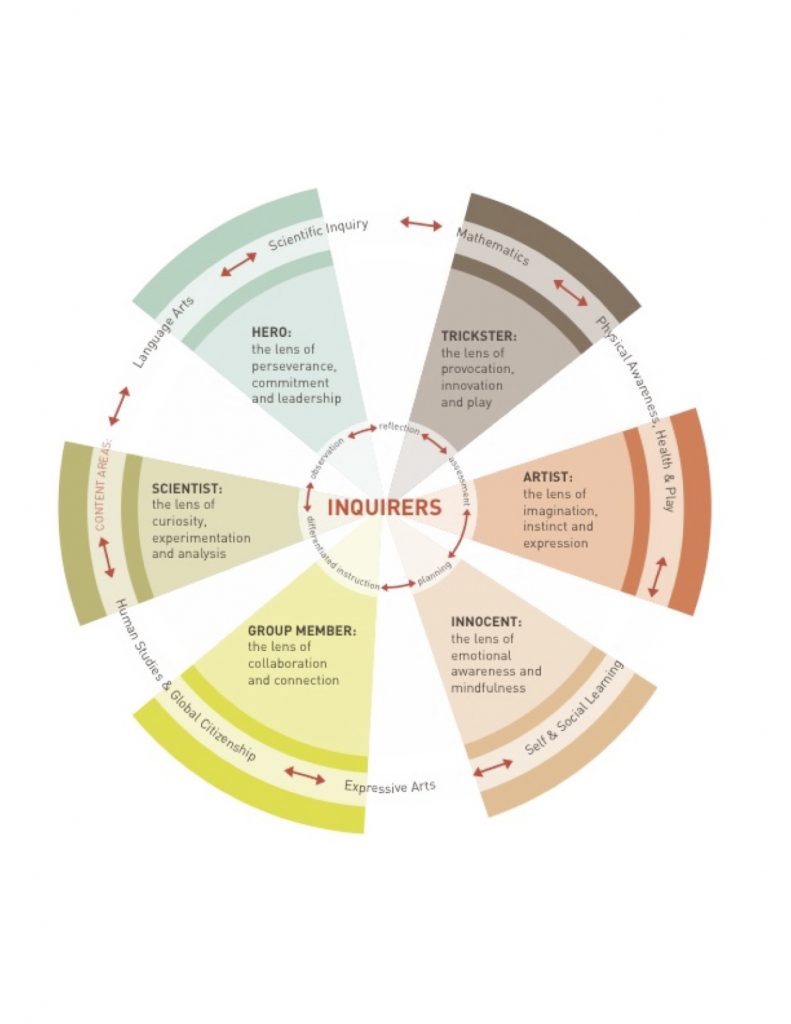

To understand how it happened, you need to begin with the idea that anchors both the Group and the School: a colorful wheel of archetypal lenses for how human beings see and make sense of the world.

As Blue Man Group and Blue School co-founder Matt Goldman puts it, these lenses evolved as the founding Blue Men designed their characters. Each pair of lenses, which are positioned opposite one another on the wheel, represent polar ways in which we are likely to see ourselves (and be seen by others). Our culture is rife with examples of the archetypal Hero, for example, yet almost barren when it comes to equivalent celebrations of the Innocent. We are more likely to value the mindset of the Scientist over that of the Artist. And despite our country’s revolutionary origins, you’re still more likely to gain points in your local community as a Group Member than a Trickster.

This is why the Blue Men, over the course of a two-hour show, spend time inhabiting all six lenses, and modeling for people what it looks like when you check All of the Above in the multiple choice question of What Does It Mean to be a Human Being. As Goldman puts it, “We wanted to speak up to the intelligence of our audience members while reaching in to their childlike innocence. We wanted to create a place where people continually learn and grow and treat each other with just a little more consideration than is usually evident out in the real world. We wanted to recombine influences to create something new. And we wanted to have a good time doing it.”

That sensibility is also at the center of Blue School, which is equal parts ritualistic, research-y, and rebellious. At weekly community meetings, for example, kids and adults take time to celebrate these different ways of being, as a way to reinforce the extent to which all six are equally valued. “I saw the Trickster in Dana yesterday,” said one young student on the day I visited, “when we walked to the park and she asked us if we had heard of any mysterious mishaps in the area.” Moments later a teacher added that he “saw the Innocent and the Artist in Mati when she was working really intently and precisely to draw negative space.”

Beyond culture-building rituals, Blue School also works proactively to translate the latest research on cognitive science and child development into all classroom practices and professional development courses. Its teachers are deeply experienced practitioners. And its initial emphasis on archetypal lenses, playful mischief, and joyful learning has since grown into what Blue School calls the Balance Model — a richly visual comprehensive learning framework that is equal parts Academic Mastery, Self & Social Intelligence, and Creative Thinking; that proclaims the school’s determination to cultivate Adaptable Thinkers, Collaborative Problem-Solvers, and Irrepressible Innovators; and that outlines Blue School’s intention to cultivate a specific set of habits of mind in its students, from Openness and Empathy to Literacy and Self-Expression.

“There are so many ingredients that have gone into making this school work,” said Farrar. “And now we find ourselves in a position where we’re able to provide all these different conditions in which different kids can flourish. That’s the thing about schools — they don’t hold a static amount of energy; the energy is exponential. And when you’re feeling creative and relaxed socially, and when there’s real clarity of expectations, that’s when it becomes magical.”

One day after school, just a few weeks into the 2018-2019 school year, I asked Blue School’s three divisional directors — Laura Sedlock (Pre-Primary), Pat Lynch (Primary School), and Laurie Kardos (Middle School) — exactly how these different pieces had come together to wield such a place. After all, it’s one thing to know an expensive private school in New York City has found a way to be magical. The real question is, to what extent is that magic transferable — to all schools, and all types of communities?

“All the things that look un-magical are what creates the space for the magical things to happen — here or anywhere else,” said Sedlock, a New York native with nearly two decades of experience in early childhood education. “Almost everything flows from our ability to answer two questions: What does it mean to really observe children? And how do we document each child’s learning more meaningfully?”

As an example, Sedlock pointed to an essential element of Blue School’s Primary program: “Big Study,” in which the children go deep on a particular subject over an extended period. Many schools have something similar, and usually, the subject of study is set in stone: the 5th grade will study ancient Egypt, the 2nd grade will study Ants, and so on. “But if we’re serious about listening deeply to children, we can’t project out that far. We have to remain nimble and go where they take us. It’s the children’s excitement that will lead to the big study, not a predetermined topic by the adults. But that requires a different skill-set than we’re used to as teachers.”

Pat Lynch agreed. “Our teachers have worked to become highly skilled at knowing that the best instructional fodder is right in front of them, and it’s unfolding in real time. Our role as leaders is to protect the space that allows our teachers to do that work. It’s very emergent.”

Indeed, emergent is a word you hear often at Blue School, and it’s illustrative of what makes the Blue School Pedagogy distinct. Spend a day there, and at all levels you’ll see students and teachers working on established courses of study — and wandering off in spontaneous directions. It’s an intellectual high-wire act — more jazz than classical — and it made me wonder what Blue School’s teachers have done to build the confidence that is required to teach this way.

“I think a real danger is to think that the solution is simply not to plan or have goals or to just give yourself over to the whims of whatever the kids want to do at any given moment,” said 4th grade teacher Ashley Semrick. “It’s the opposite, actually: it won’t work unless you have really clear goals for both individual kids and the larger group. The ability to be emergent as an individual flows from our ability as a group to have clear schoolwide intentions. Our job is to read what’s happening on any given day, and then to flexibly adjust as needed.”

How long did it take you to feel comfortable teaching this way, I asked her. “I remember back in grad school,” she responded, “someone told me that when things get rough as a teacher, you’ll just revert back to the educational standard you experienced as a student — even if that standard didn’t serve you well. Well, I can safely say that a decade into teaching, I am only now escaping that truth. It’s taken me that long to really trust that my kids always have something meaningful to say. That has made all the difference.”

“It’s taken several years for us to reach that point collectively as well,” added Laurie Kardos, who leads the school’s brand new Middle school division. “This is the first year I’ve felt like we aren’t in start-up mode. I don’t think there’s any way around that as an organization — you need to struggle with it — but for us, the work was in picking the things we wanted to align around, and then using each other to work on those things. What we’ve created is a space with the right balance of flexibility, choice, theatricality, precision, trust, compassion and autonomy. And with our experience has come a deeper ability to plan for the unexpected, not just for kids to learn something new but to become more effective at building off what they already know — and then to assess what they know not just at the end of the year but at every moment. That’s what gives this place life.”

It’s true — Blue School is alive, both literally and figuratively; even the scientists would agree. “We have discovered that the material world is a network of inseparable patterns of relationships,” writes physicist and systems theorist Fritjof Capra, “and that the planet as a whole is a living, self-regulating system. Life, then, is an emergent property. It cannot be reduced to the properties of its components. Social networks exhibit the same general principles as biological networks. What is valid for cellular life can be considered valid for any form of life. And the essence of life is integration.

“Organisms do not experience environments. They create them.”

As a result of these insights, Capra and many others — from a wide range of scientific fields — have concluded that “cognition operates on many levels, and as the sophistication of the organism grows, so does its sensorium for the environment, and so does the extent of co-emergence between organism and environment.”

There’s that word again. But what does being emergent have to do with making magic — and what needs to happen so that the magic might travel beyond Blue School’s walls?

If you ask the educators of Blue School, they’d say any recipe is a result of the sophistication of the learning culture they have steadily grown over time — the gradual mastery of technique, perhaps, that has allowed them to soar. They’d say it’s the intentional creation of a physical environment that is meant to reflect the values of the community that inhabits it. And they’d say it’s their paradoxical willingness to be both highly structured and completely free — to ground the learning in a discrete set of lenses, or to craft a a Balance Model — and at the same time to protect the space and autonomy of the teachers to go wherever the children lead them at any given moment. Consequently, to visit Blue School is to experience it not just as a school, but as an actual living organism — an ecosystem unto itself, one that is both self-organizing and self-aware.

Which leads to the most radical, and replicable, observation of all. “In a nutshell,” Capra says, “nature sustains life by creating and nurturing communities. This is the profound lesson we need to learn from nature.

“The way to sustain life is to build and nurture community” — no matter where those communities may be.

This, then, is the work.

Recent Comments