“Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes!”

— Carl Jung

A Nautilus shell and a Chameleon’s tail.

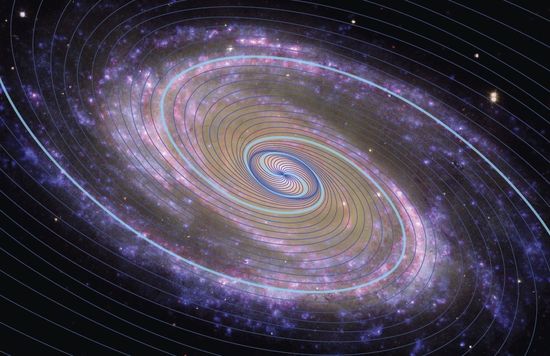

The Milky Way and the Double Helix.

A hurricane and a human finger.

The Parthenon and the Pyramids.

Or the dive path of a peregrine falcon and the propulsive power of the human heart.

All are naturally occurring designs, from the macrocosm to the microcosm. And all are based on the same universal form and formula — the ratio of 1.618 — that has been called everything from the Golden Section to Nature’s Secret Code to the language of God itself.

This is the pattern of the spiral — and it is equal parts science and spirituality, and a reminder of the inherent numinosity of the natural world.

Our awareness of the spiral goes back as far as human history can record, from its ubiquity in Stone Age art to its place in Shiva’s hand as a symbol of the instrument of creation. It is the emblem of geomancy, and the path by which we describe either upward or downward growth.

The word itself is a reminder of its deep roots in our collective memory. In Latin, the word volute, or “spiral movement,” lives on in current words we use to describe the change process itself, from evolution to revolution. In ancient Greek, the word spirare means “to breathe.” And in Sanskrit, the word for spiral is also the name of a form of yoga that relies on breath to harness the upward, circular path of tantric energy through the body and towards a higher state of consciousness: kundalini.

Despite its mystical origins, however (not to mention its ubiquitous recurrence in nature), the spiral’s spiritual significance has become somewhat lost in our modern world. But it was not lost to past generations — and if the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung is to be believed, its significance still swirls through our collective unconscious.

The rules for a spiral’s universal design are simple enough: divide a line into two parts, with one of the two parts longer than the other, such that the ratio of the whole line to the longer section is the same as the ratio between the two sections — a number that is almost two-thirds, but not quite.

.618.

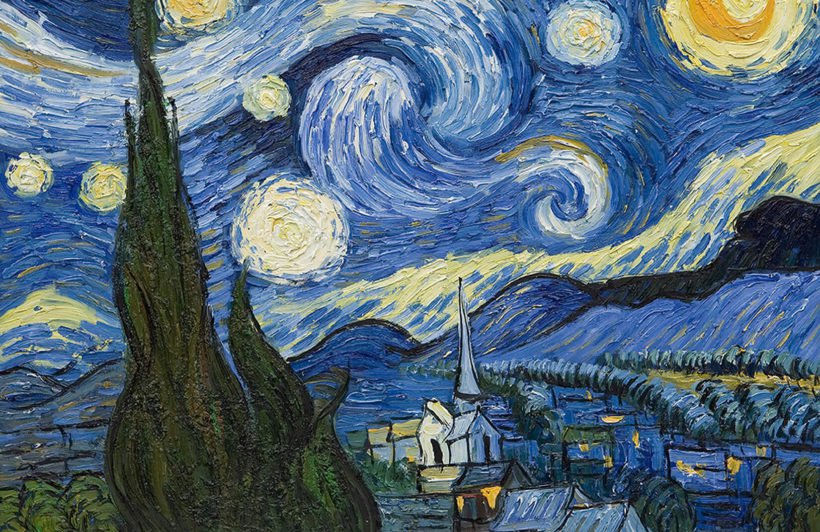

Also known as phi, this number was integral to the geometry of antiquity. It was used as a basis for the construction of the world’s most sacred buildings. It provided Leonardo da Vinci with the symmetrical structure of the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, and inspired Vincent Van Gogh’s brushstroke patterns in Starry, Starry Night.

Da Vinci also saw in the spiral’s form and function an unmatched design for the transmission of energy, as demonstrated in his hydraulic devices and Archimedean screws. And after learning from ancient Sanskrit texts about a different form for its expression — one in which the last two integers of a sequence are added together to make the next number, such that the ratio of each term to the previous one gradually converges to a limit of . . . you guessed it . . . 1.618 — the Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci helped it achieve a wider application.

Indeed, plants, animals, human beings, and the galaxies of the universe all possess dimensional properties that adhere to the ratio of phi to 1.

Why?

Its beauty and mystery comes from the fact that no one can say for sure. But close observers feel its upward circular path traces a definable pattern of movement that helps govern the one universal constant: change.

As American astronomer Lloyd Motz put it, “The stellar constellations themselves, and the almost mathematical symmetry of the spiral nebulae, are examples of forms and structures that recur time after time throughout the universe, as though there were identical moulds through space into which the matter of the universe has been poured.”

The great Hungarian journalist Arthur Koestler agreed. “There are many turns of the spiral,” he wrote, “from the slime-mould upwards, but at each turn we are confronted with the same polarity, the same Janus-faced holons, one face of which says I am the centre of the world, the other, I am a part in search of the whole.”

Recent Comments