OK. It’s a New Year. Now what?

This feels like an especially relevant question when the problems we face – in 2022 and beyond – seem so overwhelming.

Here in America, we’ve entered fascism’s legal phase. Around the world, the climate emergency advances, unabated. And for the third year in a row, the COVID pandemic rages on.

Against such odds, what are we to do?

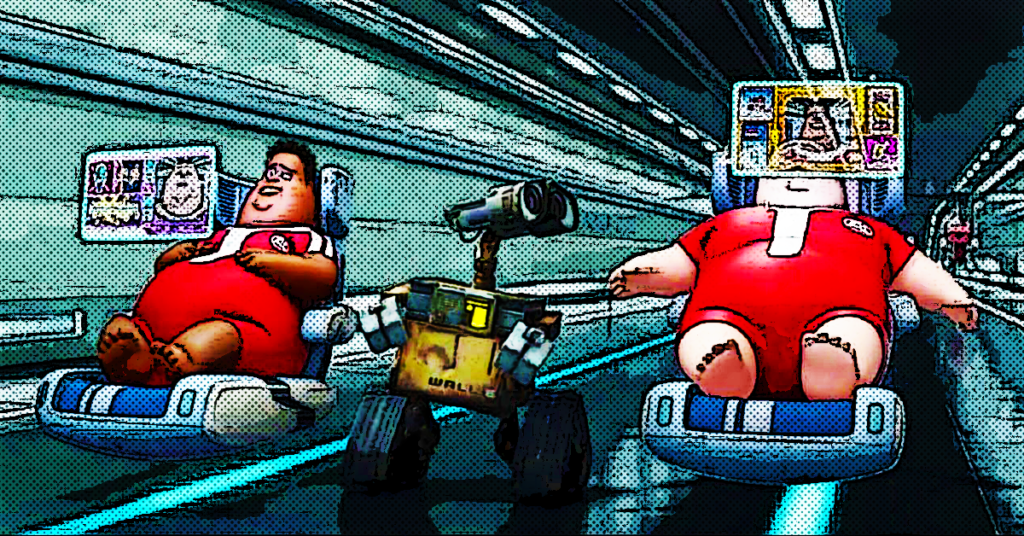

In my mind, there’s only one way to avoid the WALL-E-y soporific stupor that awaits us:

We must make 2022 the Year of the Network.

In fact, this shift has been remaking the scientific community for years; scholars in fields ranging from biology to ecology have revised the metaphors they use to describe their work, and begun to affirm, as physicist Fritjof Capra says, “that partnership – the tendency to associate, establish links, and maintain symbiotic relationships – is one of the hallmarks of life.”

Medical scholars like Dan Siegel agree. “Relationships are the crucible in which our lives unfold as they shape our life story,” he explains, “molding our identity and giving birth to the experience of who we are, and liberating — or constraining — who we can become.”

That’s not just flowery prose; it’s how living systems operate in the natural world — by existing and creatively organizing within and between a boundary of self. Although this boundary is semipermeable and ensures the system is open to the continuous flow of matter and energy from the environment, the boundary itself is structurally closed.

A cell wall is a good example. It’s the boundary that establishes its system’s identity, distinguishes it from and connects it to its environment, and determines what enters and leaves. But because this meaning of “boundary” is as much about what it lets in as what it keeps out, the end result of this arrangement, according to the German biologist Andreas Weber, is a notion of self in which “every subject is not sovereign but rather an intersubject — a self-creating pattern in an unfathomable meshwork of longings, repulsions, and dependencies.”

In the daily whir of our personal and professional lives, that means we need one another more than ever – and not just the people who make up our proximite physical pods, but those of us who, thanks to these dialectical technologies, can now foster meaningful connections (and expand our respective self-creating patterns) across miles and time zones and traditions.

“When you form groups,” writes Iain Couzin, who leads the Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behavior, “you suddenly have a network system where social interactions exist. We have traditionally assumed that intelligence resides in our brains, in the individual animal. But we have found the first evidence that intelligence can also be encoded in the hidden network of communication between us.”

This is the profound lesson we need to learn from nature — a lesson that is equally true at the smallest scale.

“In the quantum world,” explains Margaret Wheatley, “relationship is the key determiner of everything. Nothing exists on its own or has a final, fixed identity. We are all bundles of potential. Relationships evoke these potentials. We change as we meet different people or are in different circumstances.”

To that end, then, let’s make 2022 the year when we provide one another with three things in abundance:

- New Rituals

One of the most important features of rituals, psychologist Rebecca Lester explains, is that they not only mark time; they create time. “By defining beginnings and ends to developmental or social phases, rituals structure our social worlds and how we understand time, relationships, and change.”

This is why we created the Seed + Spark Network – as a space for new rituals in this highly liminal period of our lives. For all of us, life as “normal” is distinctly over. Yet we’ve yet to discover whatever our new normal will be. “So we wait,” Lester writes, “in this in-between state, betwixt and between, neither here nor there, suspended.”

We are not built to live this way – in endless liminality, with life and time unmarked.

So we need new rituals, and although each of us will have our own, I hope you’ll join us each Wednesday night throughout this new year -– when we can mark the time, make new connections, and evoke our own bundles of potential. See you there?

- New Ideas

We won’t get out of the mess we’re in by applying the same logic that got us here in the first place.

We need a new path, and a new story.

Whereas for centuries we’ve all lived under the same systemic trappings of modern life (from capitalism to communism), today we require a new kind of order, and a new source of strength. “Anything not built for a network age — our politics, our economics, our national security, our education — is going to crack apart under its pressures,” journalist Joshua Cooper Ramo suggests. “Our era is one of connected crises. Relationships now matter as much as any single object. And puzzles such as the future of United States-China relations or income inequality or artificial intelligence or terrorism are all network problems, unsolvable with traditional thinking.”

In response, we’ve designed a deck of cards for humanity that will, we hope, help you fall (back) in love with the natural world, become more knowledgeable about living systems, and apply those insights creatively to address the myriad problems that require our sustained, urgent attention.

Here they are, in digital form. Try them out, see what they spark, and share what you learn with the rest of us.

- New Relationships

Most importantly, we need one another – both those who are already a part of our circle, and those we have yet to meet.

In a living system, everything is connected. There are no parts to be exchanged or fixed. Critical connections, not critical mass, are what matters most.

How, then, can we deepen both the quantity and the quality of the connections in our lives?

“Exalted we are,” wrote the recently-departed American biologist E.O. Wilson, “risen to be the mind of the biosphere without a doubt, our spirits uniquely capable of awe and ever more breathtaking leaps of imagination. But we are still part of Earth’s fauna and flora, bound to it by emotion, physiology, and, not least, deep history.”

So let’s be more intentional in this New Year in the ways we weave ourselves together.

Let’s face the problems of the world with our collective strength and wisdom. And let’s make this a year of new rituals, new ideas, and new relationships that can help light the path to building a better world, by design.

“Behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern,” Virginia Woolf said. “The whole world is a work of art . . . Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God.

“We are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself.”

Recent Comments